Η Κατοχή The Occupation

The Occupation, or Η Κατοχή (pronounced ‘ka-to-hi’) in Greece began in April 1941 when the Nazis invaded. During the first months of the Occupation, all fuel and means of transportation was confiscated. Thus no food or supplies could be transported.

Strategic industries were seized. Commodities like olive oil, cotton, leather and tobacco were transferred out of Greece. Markets were sealed under the sign of the swastika. All fuel tanks were emptied. Poultry herds and pigeons were killed by the Nazis. Farmers were forbidden to harvest their fields on pain of death. Meat, cattle, sheep, dairy herds were confiscated by the Germans. Cars, buses and trucks were seized. Shops cleaned out and goods shipped back to Germany. Rare materials, metal, leather were also taken back to Germany. Hospital and drugstores were emptied of supplies.

Extraordinary levies were placed upon the country of Greece to sustain the occupying troops. The Greek levy was determined to 113.7% of the national income of Greece. A full naval blockade was put into place by the Germans which prevented all imports into Greece even food.

Farmers had to pay taxes and sell at enforced low prices, food price controls and rationing were tightened. Fishing was also prohibited. In Greece, the Nazis policy under the Occupation was that of plundering the country to the detriment of its native population.

In the Winter of 1941 −1942 acute food shortages existed precipitating a famine. Estimates are that 300,000 died in Athens and the surrounding area. German records show a rate of 300 deaths per day in December 1941, the Red Cross estimates 400 a day, with some days at a rate of 1,000 per day.

Raisins, olives, wild greens and rationed bread were the only available staples to eat. The hills in Greece were stripped bare. Dead bodies were left on the streets of Athens. Emaciated bodies were a common sight.

Newspapers ran advice columns to aid readers on how to survive. The columns offered such advice as chewing food slowly for longer periods of time in order to fool the stomach and advising people to collect the crumbs from the table in a jar.

In modern Greek memory the word, occupation, means famine, deprivation, and starvation.

My mother lived in Greece during The Occupation. She cooked and ate dandelion greens (what in America we consider to be weeds) as long as I remember. She never threw out food and grew vegetables in our back yard.

My Greeks who survived The Occupation relate stories of children who reached adulthood without ever tasting meat and who never become accustomed to real food.

My mother still remembers the taste of the bread made from flour sent from America at the end of The Occupation. She says bread never tasted so wonderful. When she came to American her greatest disappointment was that she could never find the flour that made bread taste so good.

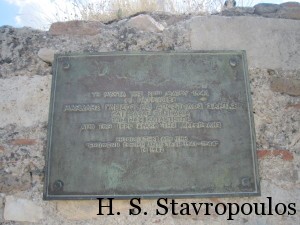

I visited the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library in Missouri. President Truman signed the European Recovery Program, commonly known as the Marshall Plan which over four years distributed food and money to assist European countries devastated in WWII. The people of Greece dedicated a statue of President Truman in Athens and sent him a helmet from the time of Pericles in gratitude. In an exhibit at the presidential library, I saw a photograph of flour sacks from American being unloaded in Greece and on display was one of the flour sacks sent to Greece. I called my mother that night to tell her I had found the flour she’d been looking for.